⚠️ Content warning: This article references, and links to, news stories that involved male perpetrated sexual violence and murder, alongside discrimination and hate crimes that affect various communities. You can read more about the ethos of this website and terms of use.

This is a long read, so here are some key points if you’re in a hurry:

- The idea that people won’t act in the face of danger, especially in crowds, appears to be myth. History, latest research and events seem to show that when the moment requires, people will and do step up

- There are a number of different ways that people can intervene safely. The 5Ds of Intervention offers useful insight.

- Fierce compassion is not about making excuses for the harm doer, but finding ways to protect the harmed, rejecting all forms of violence.

The History of ‘The Bystander Effect’

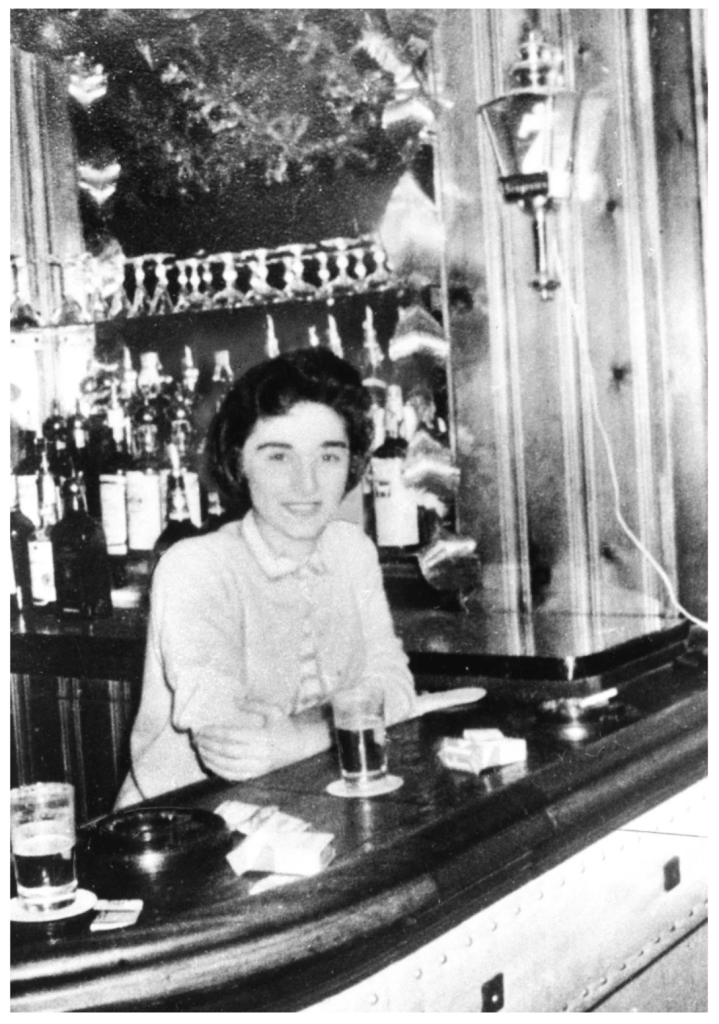

At around 3.15am on 13th March 1964, 28 year old Catherine Susan Genovese, known as Kitty, was found fatally wounded outside her home in the Kew Gardens neighbourhood of Queens, New York City.

The sexually violent assault and injuries to Kitty by a male perpetrator, which subsequently led to her death, caught wider public attention when, two week’s later, the New York Times apparently reported that 38 people had witnessed or heard the events, and did not come to her aid.

The macabre story became legend in the field of psychology, and a cautionary tale that developed in to a theory: that individuals are less likely to intervene in an emergency because, as part of a group, they feel less responsibility to act.

Subsequent analysis of the available information seemed to support this, and the suggested propensity for this type of public inaction was labelled “Genovese Syndrome” or “The Bystander Effect”.

It painted a grim picture that prompted discussion of a “morality movement”, asking the local community, and beyond, to dig deeper and do better.

But this “theory” didn’t sit comfortably with some, certainly among some New Yorkers, who couldn’t reconcile that people didn’t, or wouldn’t, act.

So when it came to light that the New York Times report of 1964 appeared to contain inaccuracies, if not erroneous claims that 38 “witnesses” did nothing, some of us looked a little closer.

Here’s what came to light:

1. People did act

In 2016, the New York Times released a statement that said:

“…the problem with the article was that some key facts were wrong…” but then went on to insist“…its broader conclusion was indisputable: that city dwellers are capable of stunning indifference to their neighbors’ life-and-death plights.”

And this is where it gets interesting.

It’s been reported by Kew Garden residents of the time, including Joseph De May Jr., a lawyer and historian, that several people did try to intervene; some by calling the police at the time of the incident, while one witness had shouted to the male attacker to leave Kitty alone – which he did, but later returned to violently assault her again.

Importantly, De May also pointed out that few (certainly not “38”) nearby residents were likely to have actually seen the attack, given that it was the early hours of the morning. Nor might they have understood that Kitty’s life was in danger. Many were likely to have been asleep, or at least half asleep, as the horrific events took place.

Another neighbour, Sophia Farrar, found Kitty after the subsequent assaults, and held her in her arms until the ambulance arrived. Farrar’s obituary in 2020, was reported to have said that, contrary to there being such a large number of witnesses who did nothing, “none actually saw the attack completely”.

Suggestions of “stunning indifference” or that people simply stood by and let a violent man end a woman’s life, now seem flawed.

2. Intervention is actually the norm

Research now suggests that the so-called “Bystander Effect” (broadly, the idea that people feel less responsibility to act in a crowd – and so don’t) might be a myth, or at least doesn’t hold water if we take in to consideration what now appears to be a different version of how events played out.

Richard Philpot and a team from Lancaster University observed surveillance footage of violent situations in the UK, Netherlands and South Africa and found, in 90% of cases, at least one person – but typically several – intervened and tried to help.

They also found, unlike the commentary underpinning the “Bystander Effect”, people were more likely to help – the larger the group – not less. This has certainly been demonstrated in acts of violence reported in the media since, where people did step up and intervene.

The disparity in the findings could be explained because Philpot’s research used actual CCTV of people stepping in at a time of conflict, rather than those trying to replicate the “Bystander Effect” through staged scenarios.

In any case, the good news is, newer research seems to show intervention is actually the norm – not usually avoided – in an emergency.

Contrary to what we so often hear, in some kinds of emergencies, people absolutely do step up and help.

Catherine A. Sanderson – Why We Act/The Bystander Effect

Proponents of “The Bystander Effect” still argue that research since Kitty’s murder proves their theory, and that Philpot’s research focuses only on those incidents which require obvious and immediate action. They say that where it’s not clear that some form of intervention is required, people may delay or decline to act.

However, the original theory stemmed from Kitty’s murder, and the associated commentary that people did nothing – which we now know at least in part, seems to be inaccurate. On that basis, Philpot’s findings are worth serious consideration. It offers hope that people can, will and do act.

This is supported by research in 2021 that suggested more than three quarters of men (78%) would intervene if they saw a woman being harassed. Or a study from Penn State that suggested the more life-saving skills you have, the more likely you are to step in.

3. Hate and prejudice as a factor

The reasons some don’t intervene may be varied and complex. As suggested, ambiguous scenarios may leave people not knowing if there even is a problem and, if so, what to do. They may feel self-conscious – or perhaps unsafe – if they misunderstand a moment. Fear and lack of safety – and training – are all valid reasons for not intervening.

So, we can agree that some individuals don’t intervene for what they may consider to be “good” reason.

But perhaps we should also then consider a potentially less palatable reason some don’t: that some bystanders may hold unhealthy beliefs and attitudes which mean when someone is being harmed, they don’t intervene because they don’t see the problem, especially if it means they can protect their own status.

In the case of a woman being harassed in public, for example, some argue that men choose not to act in these situations because of the “bro code”: that it’s not socially acceptable to call a man out, especially if no one else is doing it.

But that implies (some) men would rather ignore a harmful act towards a woman, if it means keeping a male friend onside, and implies that women – and their safety – is less important than men’s. It also suggests that type of friendship is conditional on allowing displays of misogyny, while accepting how dangerous some men can be, especially if challenged.

This attitude endorses an ideology of suprem@cy where men “perform” for other men, and where women are seen as “less than”, even if it means she then gets hurt. In the case of male violence, a key factor is that some men wrongly feel entitled, and believe they have the “right”, to harm; some may even imply their violent actions are for “the greater good”. Shamefully, in a display of mental gymnastics to “justify” his actions, when Kitty’s murderer later wrote of his crime, he said the murder was tragic “but it did serve society, urging it as it did to come to the aid of its members in distress or danger.”

Other ways this harmful ideology shows up, is where Muslim people experience Islamophobia, and Muslim women in particular are “policed” frequently for what they wear, when men generally aren’t. Where racism intersects with male violence, black women experience what’s come to be known as Misogynoir.

People in the LGBTQ+ community are subjected to homophobia and anti-trans narratives, though it’s often trans women that are in the spotlight, not transmasc people or trans men. Notions of male suprem@cy can endorse narrow ideas of masculinity and what it means to “be a man” or “a real woman”, and act as a driver for hate and violence. It can show up as someone “teaching a lesson”, or sees themselves as “being on a mission”.

The case of Eudy Simelane

It’s understood now that Kitty was a lesbian, who lived with her girlfriend Mary Ann Zielonko, although to the outside world they were simply room mates. There is currently no suggestion their relationship had anything to do with Kitty’s murder, or that it may have influenced how people responded (if there were indeed those that didn’t).

At the time of this recording, Mary Ann understandably felt people could have done more to save Kitty, based this on the media reporting of the time, not knowing the efforts of several nearby residents that have since come to light. New evidence points to the fact that people did try to help, in their own way, and that matters.

While there is no sign of prejudice in Kitty’s case, it feels important to mention here, an alarmingly common act of male violence termed “corrective ra pe”. This is the false view, held by some violent men, that lesbians need to be “cured” and, horrifyingly, that sexual violence is the “medicine”. This was cited in the murder of Eudy Simelane, a 31 year old woman and openly out lesbian who, at the time of her brutal sexual assault and murder in 2008, was on a night out in KwaThema with friends. The scale prejudice and how it shows up in male violence, mustn’t be underestimated. It’s also worth pointing out here that men are also most at risk from violent men.

Hate and harm shows up in myriad ways, and where you find one type of bigotry, you’ll often find others. Other examples include how society enables harm through prejudice towards the victim – i.e. victim blaming – and how some people, even those with good intentions, will pathologise male violence, excusing it as “he’s not well” or falsely claim “he couldn’t help himself”. Misogyny is not a mental illness.

Kitty’s killer was interrupted during the first assault, and she was alive at that point; he knew his actions were wrong and ran away. He could have chosen to stay away but he made a choice to go back. He knew exactly what he was doing and, like all misogynists, appeared to wrongly see Kitty as an object to satisfy his “needs”, or someone that “deserved” what she got. Either way, he had not “lost control”.

The Bystander Approach: Upstandership

Whether we agree on if or how people step in, we can acknowledge the importance of bystander intervention in violence prevention – known as Upstandership. This can be demonstrated in different ways, when it’s safe to do so. Imagine if society had spent 50 years focusing on preventing what Kitty’s killer did, by focusing on what he chose to do, instead of the potential myth that others did nothing. Rather than arguing the theory, we can consider meaningful approaches.

The bystander approach offers opportunities to build communities and a society that does not allow [sexual] violence. It gives everyone in the community a specific role in preventing the community’s problem…

Banyard et al, 2004

We now know that humans are not born wanting to hurt people, and can demonstrate empathy and compassion before they can even speak. Hate is taught and misogyny, in the context of this discussion, shows up in insidious ways (like a man physically moving a woman out of the way at work, or telling a woman to “watch her tone”), as well as obvious ones like sexual violence and femicide.

Intervention can look like many things – including community messaging – not simply stepping in to challenge the harm doer, and should always be done safely. Knowing what to do – and when to do it – is a key component for meaningful action. The 5Ds of Intervention offers some useful insight should only ever be done when safe to do so. Here are some examples:

- Distract – ignore the person harassing, and talk directly to the person being harassed about something completely different

- Delegate – tell someone about what is or has happened

- Document – make a record of what you can remember of the event, so that you can report later

- Delay – wait for the event to pass, but check on the person who has potentially been harmed, and see how they’d like to proceed

- Direct – call out the person harming

Violence starts long before we think it does and science tells us change is possible. When we reject narratives and harmful ideologies as a global community, we promote ways to intervene, safely; the safer the world could be for all of us, including men. If we are to prevent violence, we must address harmful beliefs and attitudes at a community level, seeing this as a moral and societal issue, not simply a psychological one. We must also consider if, when and how we act.

Whether it’s finding healthy ways to confront an abusive boss or a man encouraging a male friend to stop using sexist language, we can collaborate collectively as communities through compassionate action, to let harm doers know their harmful ways will not be tolerated.

The role of fierce compassion

Compassion itself is about recognising and alleviating suffering; in this context it’s focused on the harmdoer stopping (not explaining away what he did) and protecting the harmed.

Fierce compassion actively challenges harmful rhetoric, in a number of ways, including with humour or satire. It is not about making excuses for someone, but addressing the harm they do. It is actively calling someone or something out – Upstandership – because of the damage it’s doing, as a way to make it stop.

In all these cases, the most appropriate people to stand up to men is men.

In any event, we mustn’t forget Kitty – a young woman, with dreams of opening an Italian restaurant. Or Eudy Simelane, who was just about to start a new job at a prestigious company and, as a qualified football referee, was all set to serve as a line official in the 2010 men’s World Cup.

These women and all those whose lives have been and continue to be brutally cut short, have been subjected to male violence for no other reason than these violent men wrongly believed they had the “right” to do so. Whether people stepped in or up or not, the blame for what happened rests squarely on these men’s shoulders. And unless we keep the spotlight firmly on those men responsible, we will remain distracted from the harm they do, and it will continue.

May Kitty and Eudy rest in peace.

© The She Shout™ and The SHE course: Healing for Her™ 2025 | All rights reserved rights reserved. This article was originally published in 2023 on the If We Act website.

You must be logged in to post a comment.