⚠️ Content Warning: this article refers to male perpetrated violence, domestic abuse, sexual violence, harassment and femicide. If you are affected by any of the topics covered in this piece you may find these links (via The She Course™) helpful. The author writes from an integrated feminist, pacifist and (non-denominational) spiritual perspective. This acknowledges that people of all genders can be violent and asserts that all forms of hate are unhealthy. If the content doesn’t reflect your lived experience, readers are encouraged to set up their own website/movement on topics close to their heart, within their means, as this author has. You are also welcome to read about the ethos of this website and terms of use.

This article was originally published in 2020 and there will be more recent research which proves the points made below. However, it felt important to replicate, in the main, what was originally published (with a few amendments/additions) and why the conversation mattered then – and still does.

Let’s start with a truth we can surely all agree on: not all men are violent.

But there’s a problem if that’s only mentioned when we try to talk about male violence, particularly towards women. Just as “whataboutery” redirects the conversation towards how violent women can be, it steers the discussion away from the one we need to have – that some men are dangerous.

Of course, women know that not all men present a danger, but we can also never be sure which ones do. Sophie Gallagher, How Men Can Help

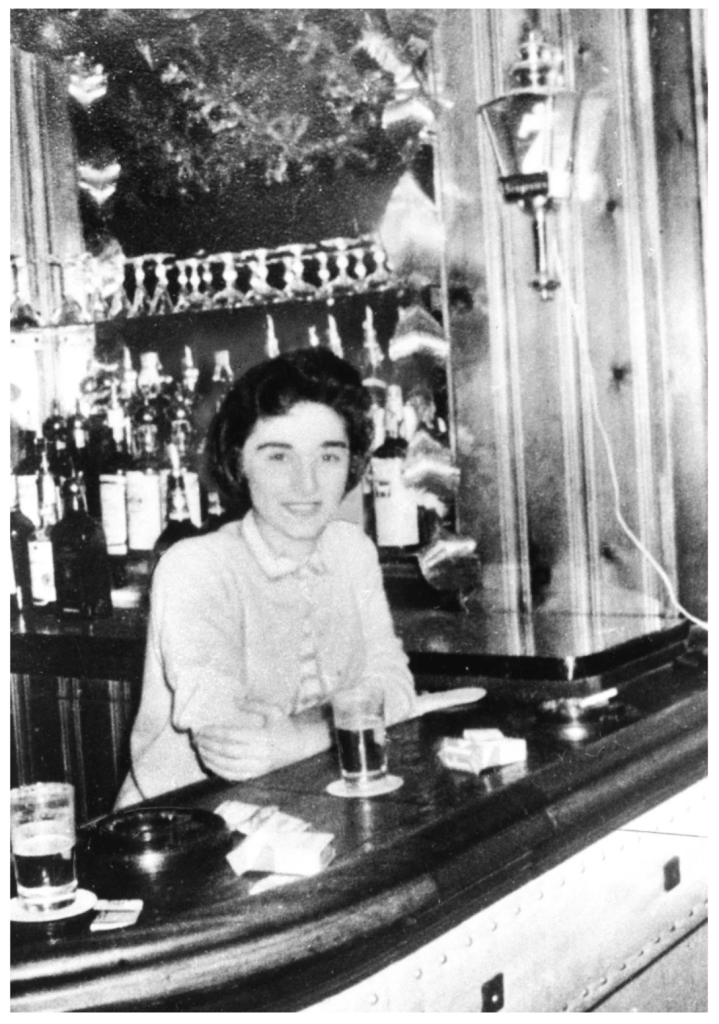

Here’s our reality: when women walk along a street, sit at our desk at work, go on a date, or visit a bar – where we should feel safe – research shows we are not.

Figures suggest that 97% of women have been subjected to sexual harassment in the U.K.. In 2017, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimated that 3.4m women had been victims of sexual assault in their lives . This included one million who had been r@ped, or had faced attempted r@pe.

If we can agree that not all men are dangerous, then we also need to acknowledge that some men are a risk. Because it’s not always obvious which ones can be, when we’re just trying to go about our daily business.

“Policing” women

Many women have “safety tools” to help them feel safe in every day life.

They’re not “over-reacting”.

They’re not being “hysterical”.

They’re not “too sensitive”.

The evidence shows women are disproportionately at risk, and have to take steps to ensure their safety.

But women’s safety as self-defence is problematic.

Women having to take these safety measures (known as “self-policing”) has become so normalised, that if they didn’t have or use these tools, they become the target for blame when they are attacked. It’s a problem because it puts accountability in the wrong place.

By saying we should “trust our instincts”, watch what we wear, not go out after dark, not wear headphones, it puts the focus – and responsibility – on women to stop men being violent.

Name it to tame it

It’s important to have space to assert that the only person ultimately responsible for hurting, controlling or killing is the perpetrator. That even though “not all men” are like that, that two women are being murdered every week by a man.

It’s important to have a conversation about male violence and why women are too scared to report and the different risks to women of doing so, including lengthy court delays, retraumatisation and fear of repercussions, whether from the harm doer or from the system that’s meant to protect the harmed.

We need to address r@pe myths like “she must be lying”, when only 4% of cases of sexual violence reported to the UK police are found or suspected to be false. In fact, figures suggest a man is significantly more likely to be r@ped by another man, than be falsely accused of that act. So we need to talk about that too … but this conversation is about women and the harm some men do.

It’s essential to be able to talk about the men who continue to harm, including those who display hate for women on social media, especially when those men wrongly feel a sense of entitlement to do so. Men who reject opportunities for love and connection, because they maintain the belief they are owed power and control, especially over women, display narrow ideas of masculinity, which harm all of us – including men.

We need to include a discussion with the LGBT+ community, including the fact that a quarter of trans people report domestic abuse.

We also need to have a dialogue about whether or not safe spaces (like refuges) are accessible for people with disabilities, and why when black women go missing their safety is neglected – and ignored – in a way white women aren’t; an example of how misogyny and racism intersect as Misogynoir. Anyone that goes missing or is attacked should be a cause for public concern – and we should be able to talk about it, and hope that people want to listen.

We need to allow this dialogue, appreciating the knowledge that men are victims too – including of domestic abuse – as well as on our streets. For those that say “but what about violence towards men?”, we can acknowledge that men matter too. But then we need to address the fact that in those cases the perpetrators are also overwhelmingly male.

90% of murderers are male and 87% of crime against the person is committed by men. 97% of sexual offences are committed by men. Where the number of male homicide victims has decreased, the number of female victims has increased in the latest year. (ONS)

A call to men

Women are not safe. And it’s time we talked about that.

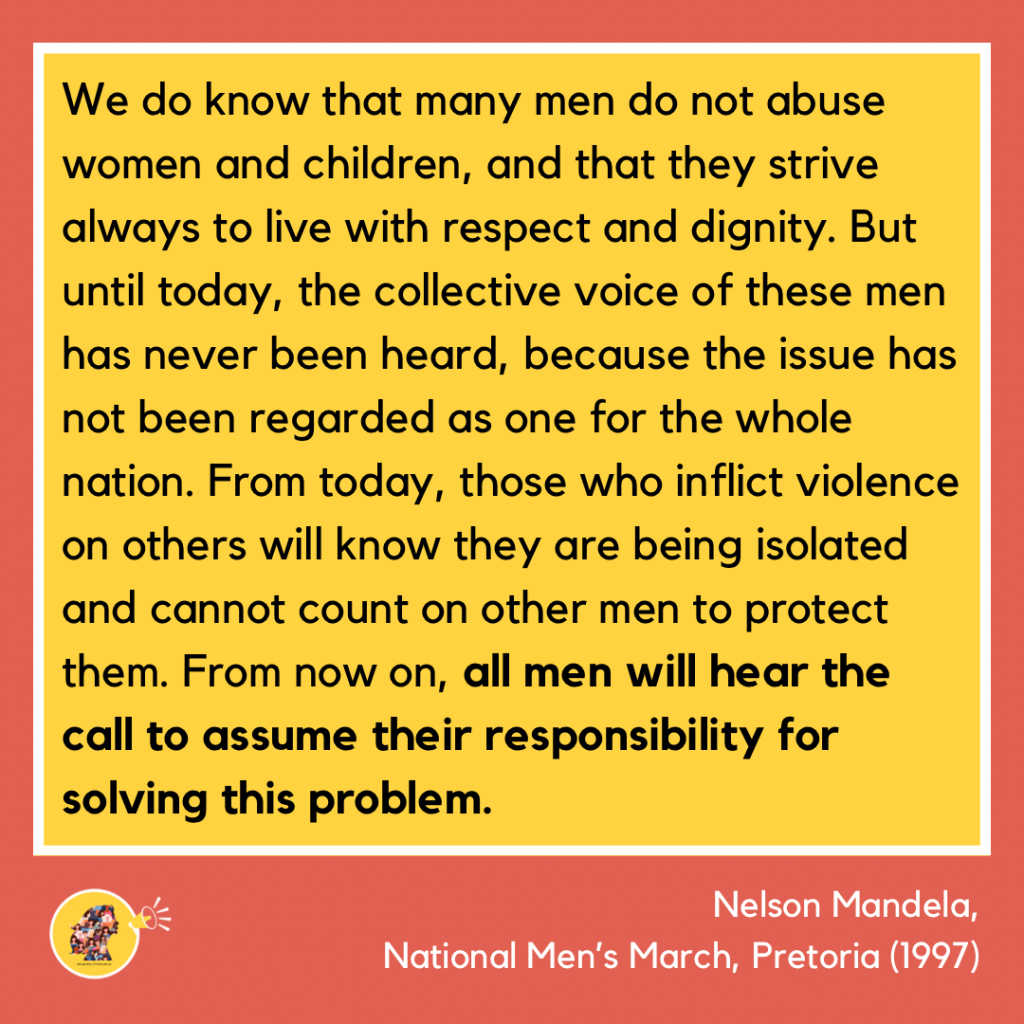

So this narrative is not suggesting that all men are “bad” or violent. It’s opening a dialogue asking men to do their part to address the problem of male violence. Not by conforming to narrow ideas of “provider and protector”, but by:

- Demonstrating empathy and compassion for this conversation. Talking about male violence doesn’t take anything away from what men go through, it actually helps them too – especially if they’ve also been harmed by a man;

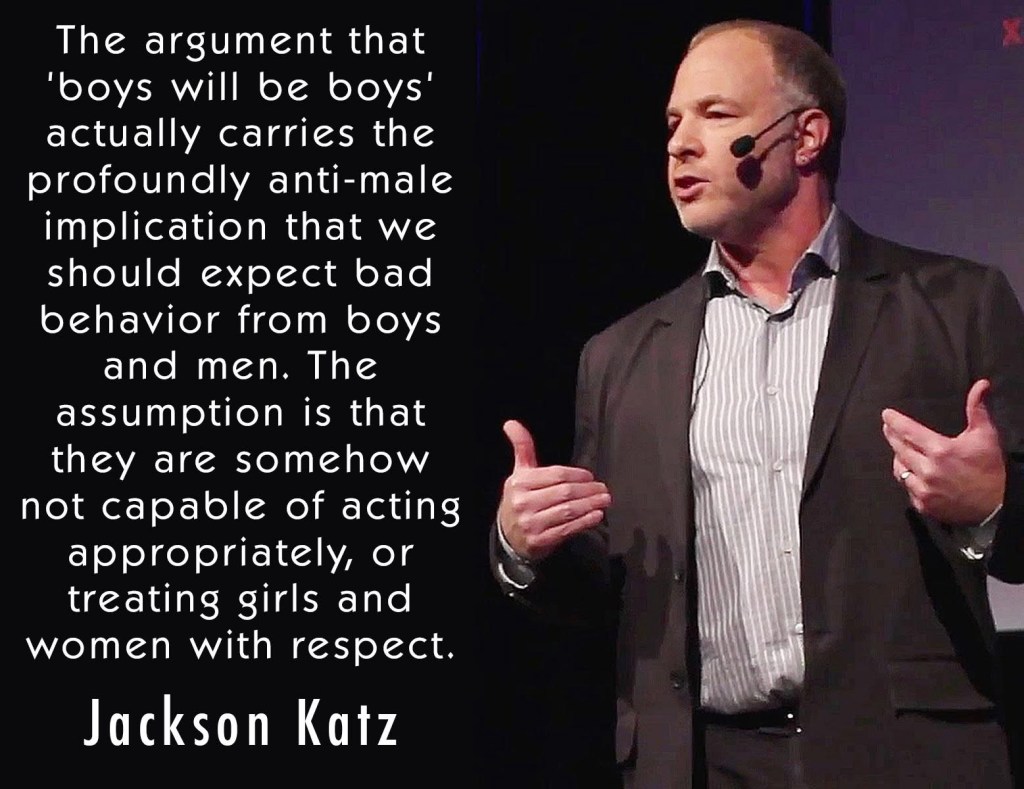

- Acknowledging and learning about the issue of women’s safety and male violence. Researchers like Chuck Derry, Paul Kivel and Jackson Katz offer important insights.

- Recognising biases about women, and addressing dominance-based beliefs of entitlement and ownership

- Not making excuses for violent men, and recognising that this is a moral and societal issue, not a psychological one. Misogyny is not a mental illness.

- Being an ally by opening a dialogue with friends and colleagues about what’s acceptable from men – or at least what’s not – in an enlightened society

- Considering interventions including upstandership, when hearing or seeing other men being inappropriate

- Recognising that “banter” about women can be a gateway behaviour, leading to other harms. Violence starts long before we think it does.

- Doing the work of emotion regulation, rather than expecting women to meet men’s “needs”

- Interrogating systems and policies at work that inadvertently endorse misogyny, like dress code or the gender pay gap

- Communicating with friends and colleagues that men don’t have the right to harm, control or kill anyone, and that all forms of direct violence – including the words men use when talking about women – won’t be tolerated.

To be an ally in the conversation around addressing misogyny and harm towards women, is to help reduce the status of men who are otherwise endorsed by the silence of a society that allows them to continue. Because so much misogynist language goes unchallenged, the assumption is that it’s ok. When men challenge abuse as it happens – when they become an Upstander, it can stop. This shows moral courage, integrity and leadership. UN Women have also written about how men can help us all feel safe.

We know men get hurt too. But this conversation is about women’s safety and male violence. And we should be able to have it. We can challenge that men will do nothing, when we know that 78% of men say they would intervene if they saw a woman being harassed.

So let’s not use phrases like “not all men”, or engage in “whataboutery” or that it’s “anti-men” to raise this issue. It minimises and derails the conversation – one we need to have – and shuts women down (an act of misogyny in itself). Otherwise we’re writing off all men as “they just can’t help themselves” when we could be saying “Yes, all men can help”.

As Jackson Katz writes in “The Macho Paradox”, “I understand women’s skepticism, who for years have been frustrated by men’s complacency about something so basic as a woman’s right to live free from the threat of violence… isn’t it about time we had a national conversation about the male causes of violence?” I think so. I hope you do too.

A world without violence is possible…if we act.

© The She Shout™ All rights reserved. This blog first appeared in an adapted format around 2020, on other sites hosted by the author, and is duplicated here for reference.

You must be logged in to post a comment.